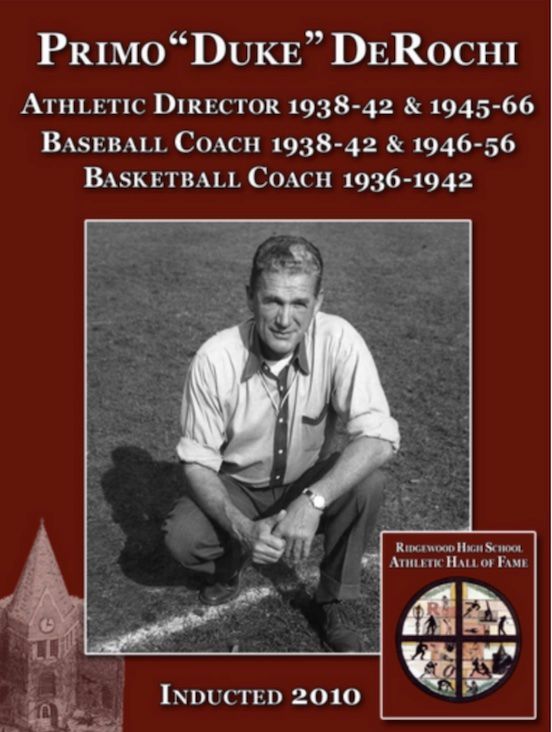

Primo "Duke" DeRochi

In 1936, Irwin B. Somerville, superintendent of the Ridgewood school system, hired Primo “Duke” DeRochi to coach boys basketball at the high school. The basketball team needed a lot of help, having won only one game in the previous two seasons.

In his first year as coach, DeRochi moved the team from last to second place in the division. In 1943, the Maroons finished first in what was then called the Northern New Jersey Group Three League.

When Howard Richardson, then athletic director and baseball coach, left Ridgewood in 1938, DeRochi took over as athletic director and began a 15-year tenure as baseball coach.

DeRochi died on Oct. 9, 2003 at his home in Venice, Fla., one week short of his 98th birthday.

During his tenure as head baseball coach, DeRochi worked with a number of gifted players, including Harry Grundy, who, as his ace pitcher, helped him win back-to-back championships in 1940 and 1941, and Don Haldane, a star in football, basketball and baseball, who died in World War II.

DeRochi dedicated himself to athletic fitness at all levels, In addition to his coaching responsibilities, he also served as fitness trainer for the football team. In 1942, he introduced a strenuous calisthenics program, including rope climbing, track workouts, pull-ups and coordination drills in all boys gym classes. DeRochi knew many of them would be called on to serve in World War II, and he wanted to make sure they were in top physical shape.

A year later in 1943 at the age of 37, despite having a young wife and two growing boys at home, DeRochi answered his country’s call and joined the Navy as a lieutenant. Stationed in the Pacific, he participated in the amphibious landings that put the Marines ashore at Iwo Jima and Okinawa before returning in 1946 to Ridgewood, where he resumed his responsibilities as director of athletics and baseball coach. He continued coaching baseball until 1956.

DeRochi also served as director of the water safety program at Graydon Pool for 18 years and teamed up with a friend in the operation of a small grocery and delicatessen on East Glen Avenue in Ridgewood.

A native of Waterbury, Vt., DeRochi graduated from the University of Illinois in 1928, but when his best teaching job offer turned out to be a $1,400 post in Southern Illinois, he decided to go for his master’s degree, which, in 1929, earned him a teaching job in the Glen Rock school system for a salary of $2,000 a year.

“That was fantastic pay in those days,” DeRochi recalled in an article published in The Record on June 2, 1966. “Most of the teachers were starting at $1,200 right out of school. I got a $100 raise each year, and in two years was making $2,200. But then bad times set in, and I had to give back 20 percent, so that after three years in the system, I was making less than when I started. The main thing was that I was working, and I didn’t care what they paid me as long as they continued to let me work. You’ll recall that in the early 1930’s, there were a lot of people who couldn’t get work for any kind of money.

DeRochi remained in the Glen Rock school system until 1936, when he moved on to Ridgewood.

His leadership abilities did not go unnoticed. In 1953, he accepted an appointment to the New Jersey Scholastic Athletic Association and became president of the group a year later. In 1956, he served as president of the Bergen County Coaches Association.

On June 8, 1966, DeRochi retired from Ridgewood High School, having served almost 30 years (1945-66) as athletic director. About 150 men who either played on his basketball or baseball teams or were in his physical education classes gathered at the Suburban Restaurant on Route 4 in Paramus to pay tribute to DeRochi’s accomplishments. The event was chaired by Warren Byrne and Dr. Mario Ferraro.

Ed Van Tassel, who pitched for DeRochi in 1940, spoke of him as a leader and an inspiration, a man they reverently called “Coach.”In 1966, DeRochi took issue with those who felt that participation in athletics interfered with an athlete’s scholastic work.

“A boy goes out for a team and develops the habit of working according to schedule,” DeRochi said. “He has to watch his marks, or he becomes ineligible. His sports activity takes about two hours a day, and he learns to budget his time. The boy who is active in no extra-curricular program of any kind gets into the habit of wasting his time and, more often than not, has more difficulty with his studies than those who are busy with other activity.”